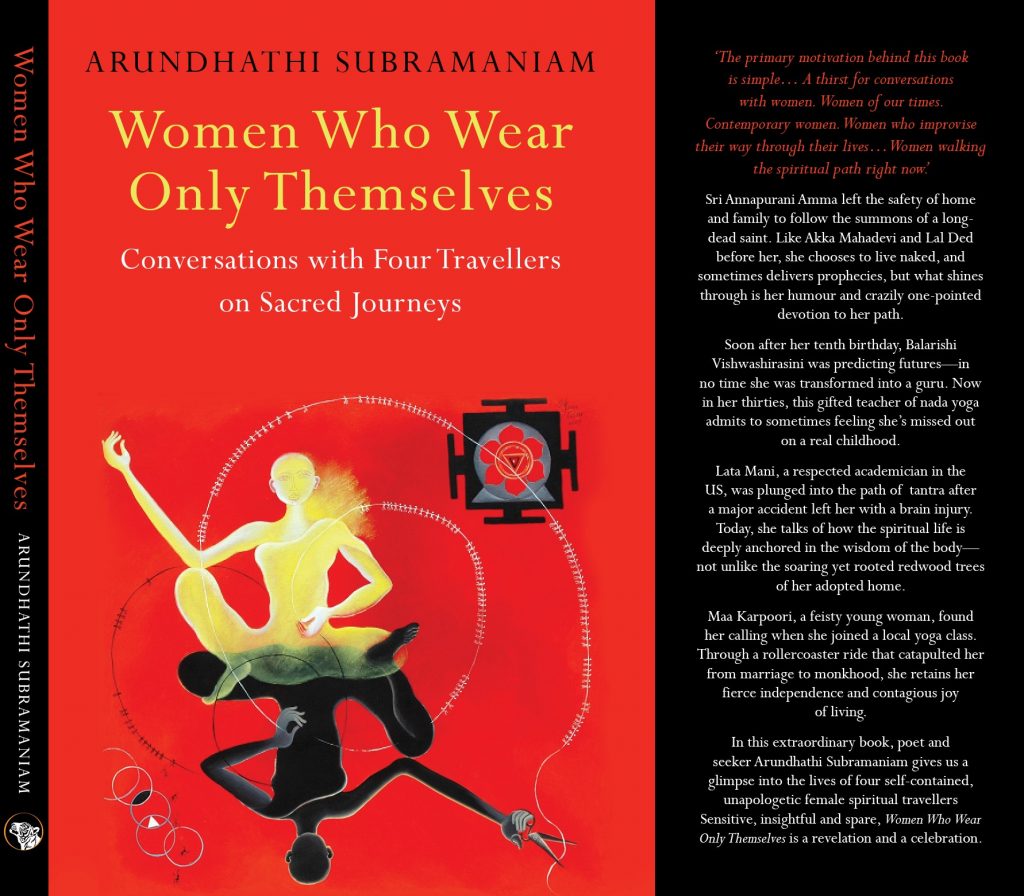

Arundhathi Subramaniam

Speaking Tiger Books LLP, 2021,

499 INR

As I read the introduction to Women Who Wear Only Themselves, I was reminded of a book by yet another Arundhathi- Arundhathi Roy and the iconic title of her debut book, The God of Small Things. The God of small things- the one who watches over the ants, the beetles and other little creatures- does not get massive temples or frenzied, opulent rituals. That god exists in relative anonymity and in the truncated lives of his devotees. But it’s a reassuring god. A comfortable god.

This is the sort of divinity that Arundhathi Subramaniam brings her readers. Published in 2021, the full title of the book is, Women Who Wear Only Themselves: Conversations with Four Travellers on Sacred Journeys. As the title promises, the book contains Subramaniam’s engagement with four female mystics. These engagements are at times chance encounters that evolve into deep spiritual relationships and lead to engrossing introspections on the ways that people can exist.

Spirituality in India is a multi-billion dollar industry, with some spiritual leaders amassing massive followers and fortunes. There is a huge demand for wise words, sayings and tangible symbols of spiritual affiliation. And the more contemporary a guru is, the greater the following. It is into this cosmos of noise that Subramaniam tosses a bubble of silence. The four women she writes about are not at the centre of the spiritual industry, they are not owners of media houses or million dollar educational and industrial conglomerates, rather, they are women whose vestments or the lack thereof (in the case of Annapurani Amma), points to an essential innocence. These goddesses of small things are individuals whose connect with the cosmos and themselves makes them self-sufficient. They require no hordes of devotees to assure them of their powers.

Arundhathi Subramaniam brings four spiritually awakened women- Sri Annapurani Amma, Balarishi Vishwashirasini, Lata Mani and Maa Karpoori into our midst to ask us to redefine our ideas of what spirituality may mean.

Each of these women have their own means of connecting to the universe and have made their peace with the realities that surround them- be it skepticism, the expectations to ‘perform’ spirituality as per the imagination of the people or the singular focus demanded by monkhood. Subramaniam has brought each of these personae to life by pointing out their core philosophies, laying bare their vulnerabilities and narrating them as they are.

Women Who Wear Only Themselves is a brave book. It presents without judgement and seeks to speak truths. The authorial voice, which also acts as eyes for the readers, is an impartial one. It intercedes, introduces, expresses doubts, seeks to find the horizon. There is no hagiography. Each section of the book is extraordinary in that it presents women in different stages of their lives, experiencing the Divine or the Universe in their own way- be it through the ardent devotion to the Guru as with Annapurani Amma, the music of the cosmos – as with the Balarishi, the understanding of stillness and the revelation it can bring as with Lata Mani. In the segment titled What it takes to be Redwood Tree, Subramaniam quotes Lata who reveals that the Devi asked her to be like the Redwood tree.

‘The roots of the redwood are shallow but the network is horizontally extensive and extraordinarily resilient. At the same time, the vertical trunk shoots determinedly skyward, while the branches plane towards the earth. It is a perfect image for the rooted dis/passion of the tantric way. We are fully present on earth, densely connected to each other, and equally to that from which we came, and to which we will return.’

Subramaniam then goes on to observe,

That image has stayed with me. The redwood tree as an axis between temporality and foreverness. Between earth and vertigo. I am reminded too of a couple of lines in Lata’s book: ‘Truth is merciless. It demands that we not set up residence anywhere, but remain ever ready to resume our journey onward.’ (128)

Women Who Wear Only Themselves carries within it the power that these women exude. Their uncomplicated assurance and belief in the Goddess and their spiritual guides. They speak of visitations from gurus and saints who are hundreds of years old- their devotion is unshakeable and doesn’t rely on showmanship for garnering devotees.

The segment on Maa Karpoori A Leap into Monkhood, is where the author is at her intimate best. There is a sense of the autobiographical. The introspective tone reveals vulnerabilities of the sort that have often crossed our minds as well.

I relate to the idea (even if I don’t feel called to live it) of paring away inessential identities, of giving up the seductive daily jugglery of roles—employee, offspring, spouse, parent—that we are encouraged to believe is the excitement of human life. Outsourcing one’s material anxieties to a monastic order to lead a life of social engagement or contemplation also makes sense to me. Simplifying life makes deeper sense still. (135-36)

This book is also illuminating for one who is interested in knowing what Subramaniam considers Bhakti. Considered one of the most strident voices of the modern day Bhakti tradition, it is heartening and encouraging to have Subramaniam speak of Bhakti outside of any specific ideology or as a regimented, unimaginative way of life. Bhakti for Subramaniam seems to be freedom from the fetters of hierarchy. It is a beautiful communion with the Self and with Nature.

For bhakti is not obedience, as many believe, but commitment—and commitment not to a person or a belief, but to an unfolding inner journey. And as the journey deepens, one of the most extraordinary discoveries the bhakta makes is that surrender is not one-sided, but deliciously mutual. (158)

It is this surrender that creates these extraordinary women who wear only themselves. Their voices are like hurricanes and their eyes see everything, their minds are unafraid. Take this exchange between the author and Maa Karpoori:

I turn to Maa. ‘How would you describe monkhood?’

‘When what is unnecessary falls away, and only what is absolutely needed remains. When everything is yours and nothing is yours.’ (161)

Sometimes, as a reviewer, I feel it is best that the author themselves speaks. For all the words that I have written above, Subramaniam sums up the soul of her work beautifully, succinctly.

If this is a book about language, it is also one about attire. A recurrent trope is clothing: Annapurani Amma’s nakedness; Balarishi’s journey from ochre to denim; Lata Mani’s search for a verbal fabric that combines the cellular and the cerebral; Maa Karpoori’s embrace of her monk’s apparel. There is a process of weeding, of stripping down, paring away needless acquisition, sheaths of unexamined habit, that each traveller speaks of, in order to find herself. There is also a process of crafting a new garment, a new wordskin—lighter, airier, less stiff, more porous—into which personal discovery as well as insights garnered from other sources and traditions are internalized, woven in. Which makes this, at heart, a book about language as chosen attire—a way of wearing the self.

Poetry is a language of concealment and revelation. It offers meaning as well as a respite from meaning. A shadow-light weave of layering and unveiling, of mystery and clarity.

And that is how I see these women. Not as case histories to be proved or disproved, but as weaves—of sun and shade, semantics and silence, suspended between logic and lyric. Their language ranges from the dense to the sheer—sometimes Persian carpet, sometimes pure pashmina. (167-168)

The book is interspersed with poems that reflect the soul verse of the book.

Goddess II

after Linga Bhairavi

In her burning rainforest

silence is so alive

you can hear

listening.

While the book talks of four women in conversation, it will strike the reader that there are actually five women who are equally invested in their search of the Divine. The Goddess, Energy, Cosmos, Eternity- call it what you may, courses through the veins of the five seekers. It may finally dawn on the reader that in her own way, the author too might be wearing just herself. In the twilight hours or in the quiet hours of the dawn, when we feel a shift in the Cosmos, it makes us aware of the immensity of the canvas that we face. The ensuing wonder and humility are what Subramaniam brings us through this book- that- and the lives of truly remarkable women.

Sonya J. Nair

Editor

A reader response by Shabnam Mirchandani can be read here.

Leave a Reply