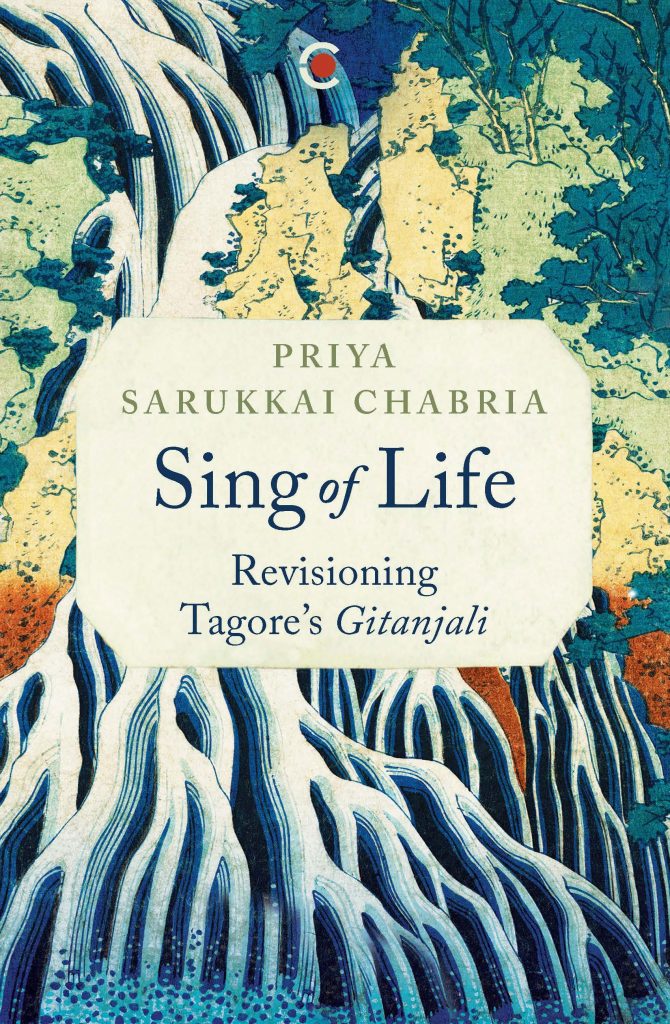

Priya Sarukkai Chabria.

156pp, ₹499, Context (Westland), 2021

Since its publication in 1913 and the subsequent award of the Nobel Prize for Rabindranath Tagore, Gitanjali (1913) has remained alive and relevant in the collective consciousness of Indians as a text that, apart from defining Gurudev, as Tagore is popularly known, symbolized the validation of the cultural and intellectual wealth of the subcontinent. In the West, Gitanjali, captured the attention of W.B Yeats, Thomas Sturge Moore and William Rothenstein, among others, creating an aura around Tagore, the glow of which refuses to fade to this day.

The resultant dominant image of the mystic-philosopher that surrounds Tagore often obscures the lasting concerns he had about Nation, nationalism, Art and the role of the Artist. The soul search that is the hallmark of the artist and the quest for an elusive beauty that appears only through art has been a pivotal point in informing Tagore’s enunciation of the Divine. It is this quest that poet and novelist Priya Sarukkai Chabria joins as she attempts a revision of the Gitanjali.

Sing of Life is many things at once. It is a tribute. To the great and wonderous vision of the Gurudev which revels in the exquisiteness of the Cosmos. It is a reimagining of Gurudev as one who sings in rapture like the Baul singers or the Bhakti poets who saw the Eternal-as-Beloved and outside of the confines of gendered semantics. Sing of Life is an act of love, one that sees and celebrates the best of this Beloved. It is an act of veneration, one that stems from Chabria’s own spiritual philosophy. As with her landmark work on Andal, the eighth century Bhakti poet, here too, Chabria commits her heart and soul to this revisioning.

At the very outset, the book lays out its purpose in a wonderfully readable and erudite introduction by Chabria herself, wherein she speaks of the very personal process that helped articulate the poems. Reading the account gives one the idea of the intricate and organic methods that the best translations benefit from. That Chabria reveals her process through examples from the book points to a selfless desire to help others commit to this process and perhaps take this work further. This is commendable and I must say, in keeping with the spirit of Gitanjali that sees knowledge as free and unfettered.

Chabria too has 103 poems in her book, just like the original. What she does with them is entirely another matter. She has read into the soul of these poems and distilled their essence. Where Tagore translated Gitanjali into English as a series of prose poems, Chabria brings us verses from those very lines. She does not, she says, “alter his word order, nor interpolate…I will stay with the present tense to honour the work’s energy. I stay with the thrall.”

There is a sense of urgency and immediacy that informs Sing of Life, one that can only come from an intuitive knowledge. And this intuitiveness is what informs the purity of purpose of this book. Chabria employs juxtapositions, connectives, singularities to Tagore’s lines and presents lines of rare luminosity. She writes Tagore in the language of the present day. The book is a palimpsest – layers upon layers of meanings that come through the process of repositioning the words to form a new pattern of ideas. It is a symphony being performed by two people across Time.

For me, what sets this book apart is the freedom it embodies. The interiority of the journey undertaken together by Tagore and Chabria makes the work one that espouses spiritual liberty. It is a full-throated song of a bird at dawn, the gurgle of a river that refuses to obey. And like John Donne, even when she is done, Chabria is not done. Beneath every poem that she has translated from Tagore, are her own readings – austere in their composition, seismic in their impact.

One cannot help but admire the monumental work that has gone into the book in terms of chiseling away at the songs, particularly ones as lengthy as songs 41, 48, 51, 52, 60 and leaving behind a structure through which light enters, forming interesting patterns. These patterns become very visible on the page through the white spaces that Chabria leaves between words and lines. These line breaks do not indicate rupture. Rather, they are pauses for the readers to contemplate and respond. These are meditative spaces, in which everyone is a poet, everyone bathes in the benign light that wafts in. Chabria foregrounds the elemental aspects of Tagore’s work – rain, sunlight, air, dust, darkness – all find a home in these pages.

It is a cathartic experience to read Sing of Life on account of the unbridled, molten passion and devotion that stand revealed. The book also contains the text of the Gitanjali and when each reading is placed beneath Chabria’s work, it creates a stunning overlay – a route map to the very core of being. The words that she saw, chose, was inspired by, listened to – the patience and dedication of making those choices – fills one with a sense of wonder and humility. She sheds the weight of the Thee and Thou and chooses a more intimate You, bringing the Divine closer as in the Bhakti tradition.

For when

Ever in my life have I sought thee with my songs. It was they

who led me from door to door, and with them have I felt about

me, searching and touching my world…. (excerpt from song 101)

becomes

I have sought you

With my songs With them….

one has to sit back and catch one’s breath at the economy of words, the expansiveness of imagination and the sonic effect of the pause. And then as a bolt of lightning, at the end, separated by the tiniest of marks, comes what Chabria found “floating”- another facet to the gem.

with

my songs

i feel about

searching, touching

guide

me to

the mysteries

Sing of Life is a book that treats its pages as a sanctuary, as places of peace. In a way, it is an epigrammatic expression of the life and message of Gurudev. Chabria comments that while working on the book, she started with Tagore and ended with Gurudev. The same might be the case for readers as well. I love the way Chabria reads the celebrated introduction to Gitanjali by Yeats,passing it through the same process as the poems- indicating consistency, but also being delightfully cheeky! The book is tastefully designed and the attention to detail in the cover design and inner pages heightens the sense of aesthetic awareness.

In these days of self and state-imposed incarcerations, when human contact is at a premium, when one needs a sense of connect, Priya Sarukkai Chabria’s Sing of Life come to us crossing a century-old ocean, bringing with it the beating heart of a Bhakti poet, the rhythm of his raptures on a page inked in a language that is of the present and yet timeless.

Sonya J. Nair

Leave a Reply